Richard Wright

“…for white America to understand the significance of the problem of the Negro will take a bigger and tougher America than any we have yet known. I feel that America’s past is too shallow, her national character too superficially optimistic, her very morality too suffused with color hate for her to accomplish so vast and complex a task.” – Richard Wright, Black Boy (American Hunger), 1944

I finished reading Wright’s autobiography on the day that Black Lives Matter activists and supporters gathered under the hashtags of #BlackLoveFriday and #NotOneDime to shut down one of Chicago’s biggest shopping stretches on retailers’ biggest holiday of the year. Though it was clear to me that not every shopper got the point of the protest, I was incredibly glad to see the connections being drawn between the way the US economy is run and US oppression of people of color.

In the context of the portion I have quoted above, Wright is reflecting on the white women he worked with at a cafe in Chicago. He found himself unable to bridge the gap between his life experiences and their concerns in their own lives. He continues:

“I know that not race alone, not color alone, but the daily values that give meaning to life stood between me and those white girls with whom I worked. Their constant outward-looking, their mania for radios, cars, and a thousand other trinkets made them dream and fix their eyes upon the trash of life, made it impossible for them to learn a language which could have taught them to speak of what was in their or others’ hearts. The words of their souls were the syllables of popular songs.”

His words brought into stark relief the confusion of the shoppers denied entrance to their stores: yes, we agree with your aims, but why are you blocking our sovereign right to spend money? How does police violence connect to stopping Black Friday sales?

Yes, it’s about disruption of “life as usual,” but it’s also more than that. It’s a call to realign moral values. It’s a plea to cease constant bargain-looking, running on the hamster wheel of consumerism that makes things cheaper and cheaper so that they are more readily replaced, trapping poor people in a vicious cycle of spending more money overall to stay afloat and wealthy people in a cycle of constant keeping up with the Joneses. Constant fear for our own jobs and money and savings keep us immobile in the face of state violence, prop up anti-immigrant and refugee hysteria, lead us to support constant war on black and brown bodies at home and abroad.

In another article I read recently, Arundhati Roy writes about her conversation with Edward Snowden and Dan Ellsberg, concluding: “We’re told, often enough, that as a species we are poised on the edge of the abyss. It’s possible that our puffed-up, prideful intelligence has outstripped our instinct for survival and the road back to safety has already been washed away. In which case there’s nothing much to be done. If there is something to be done, then one thing is for sure: those who created the problem will not be the ones who come up with a solution. Encrypting our emails will help, but not very much. Recalibrating our understanding of what love means, what happiness means – and, yes, what countries mean – might. Recalibrating our priorities might.”

If we’re more concerned about our ability to participate in consumerism than we are with the deaths of human beings at the hands of a force that is supposedly designed to protect them, our priorities aren’t straight. I’m afraid that one of the reasons working against racism is so difficult is that, as Wright attests to in his works, racist attitudes and behaviors of white folks are just a part of what the US is built on. Our current economic system is incompatible with an anti-racist agenda–it has nothing in it designed to care about such issues of justice. Wright predicts:

“If, within the confines of its present culture, the nation ever seeks to purge itself of its color hate, it will find itself at war with itself, convulsed by a spasm of emotional and moral confusion. If the nation ever finds itself examining its real relation to the Negro, it will find itself doing infinitely more than that; for the anti-Negro attitude of whites represents but a tiny part–though a symbolically significant one–of the moral attitude of the nation. Our too-young and too-new America, lusty because it is lonely, aggressive because it is afraid, insists upon seeing the world in terms of good and bad, the holy and the evil, the high and the low, the white and the black; our America is frightened of fact, of history, of processes, of necessity. It hugs the easy way of damning those whom it cannot understand, of excluding those who look different, and it salves its conscience with a self-draped cloak of righteousness.” (bold emphasis mine)

To change, we’d have to admit that our economy is built on slavery and genocide. We’d have to admit that the lifestyles we so idolize in this country are not attainable by all – and never have been. We’d have to admit that our concept of our own success means others not, or never, succeeding.

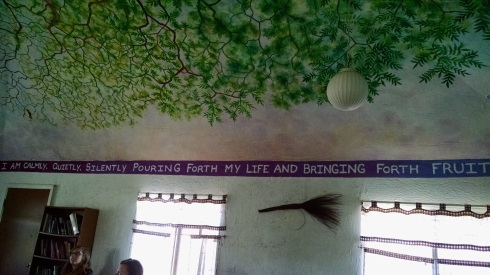

But I think this is the direction that Wright pushes us. He concludes at the end of Black Boy that “in all the sprawling immensity of our mighty continent the least-known factor of living was the human heart, the least-sought goal of being was a way to live a human life. Perhaps, I thought, out of my tortured feelings I could fling a spark into this darkness. […] I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all, to keep alive in our hearts a sense of the inexpressibly human.”

I cannot possibly claim to understand the forces that moved Wright, from my position as a white person in this country today. But the call I see him making to all of us is the same expressed by those protesters on the Mag Mile: we invite you to recognize the lives out here, being stolen, dying. We invite you to recognize the hollowness of constant shopping, obsession with things and prices. We invite you into a deeper relationship of being human, if you are willing to step outside the quick-and-fast comfort of spending money, of thinking you can control your environment if you make enough cash, if you buy the right things, if you live in the right neighborhood.

It means work, and tears, and uncertainty, but it also means answering a deeper hunger, to community and love and being together. It means trading fear of difference for struggle into love.

The connections I am writing about here are not new. I am indebted to the ideas of courageous writers & thinkers today, like Ta-Nehisi Coates and Brittney Cooper and Michelle Alexander and Mia McKenzie; of others before them, like Audre Lorde and James Baldwin and bell hooks and Sojourner Truth. I do not wish to claim credit for ideas; I wish to spread them further in vision for a different world.

I draw these ideas out because I think Wright is right; if we persist within our current economic framework, the current path that this society has set out for us (go forth and make money, be fruitful and multiply dollars, buy to save the country from terrorists), we cannot come face to face with racism in this country. We cannot come face to face with the thousand shallow values that make up American consumerism because to do so would be to bite the hand that feeds us (even REI’s campaign to shut down its stores and extort people to go outside and enjoy nature is a sales ploy; come and enjoy these rocks in the sun, we have the perfect shorts for you to do so; we sell happiness in the form of khaki trousers).

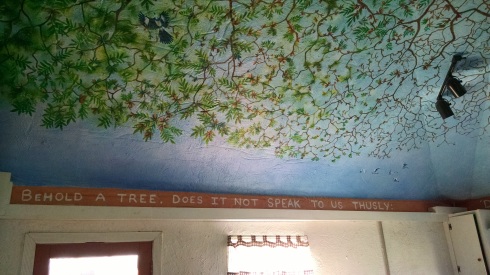

I say this to acknowledge the difficulties inherent in the road before us; I also say this because I think we can do it. I am surrounded by people, in this house at QVS and in my work at L’Arche, who work with visions for a different world. I am encouraged by all the wonderful work that my friends in far-flung parts of the world are doing to make this world more livable for everyone.

One of the reasons I came to QVS eager to live in a community was to see how we could possibly set up something that might run counter to these systems. I am excited to continue to explore this with all the people in my life.

And I say this because I want to have a conversation with you. I want to understand what you hunger for and what holds you back. I want to know the things you long to talk about, but can’t. I think we can live together in this world, that there will be enough for all of us. I will share some of this vision in subsequent posts, reflecting on some things that L’Arche has introduced me to: the Rules of Cooperation.